It is evident that the primes are randomly distributed but, unfortunately, we don’t know what ‘random’ means.

~R. C. Vaughan

The Problem we are interested

Here’s an age-old question consider a sequence of prime numbers

This question is quite critical to deal with. But just because this question is a little bit critical, it does not stop us from exploring the various things about distribution primes. Prime numbers are one of the simplest yet most complicated and confusing topics in mathematics.

Euclid Theorem

Let’s start from the basics in middle school we learned that any number can be factored into prime numbers. For example, 30 can be written as

“There are an infinite number of primes.”

Let’s quickly go over a proof. This proof is actually pretty interesting. We have used proof by contradiction. We have assumed that this statement is false i.e., there are finite number of primes.

Let P be the product of every single prime number.

Let Q = P + 1

a) If Q is prime, then contradiction.

b) If Q isn’t prime then one of its prime factors p

Let’s look at one of those prime factors

The Euler Product Formula

The Euler’s product formula generally defined as

Series

A series can be highly generalized as the sum of all the terms in a sequence. However, there has to be a definite relationship between all the terms of the sequence. If think a bit deeper it’s actually cumulative sum of a given sequence of the terms. It’s obvious a series can be finite or infinite.

Now let’s talk about harmonic series which we write as,

The p-series will always converge when

Essentially, the zeta function gives the

So you can see the right side every single multiple of 2 in the denominator. So if we want to remove that from the original zeta function. So, next step we just subtract equation 2 from equation 1

Then we’re going to repeat same process. So we’re gonna multiply both sides by the second term of the series now which is

and we have these terms and then we subtract them from the equation 3 then we’ll have,

So, we do this process again and again you’ll see that every time we do this we are subtracting multiples of each number so the second term in our sequence is always going to prime and if we continue this process to infinity we will get something like this.

and if we move all the primes to the other side writing this formula we will have,

Prime Counting Function

The idea of the prime counting function is pretty simple. The prime counting function is the function

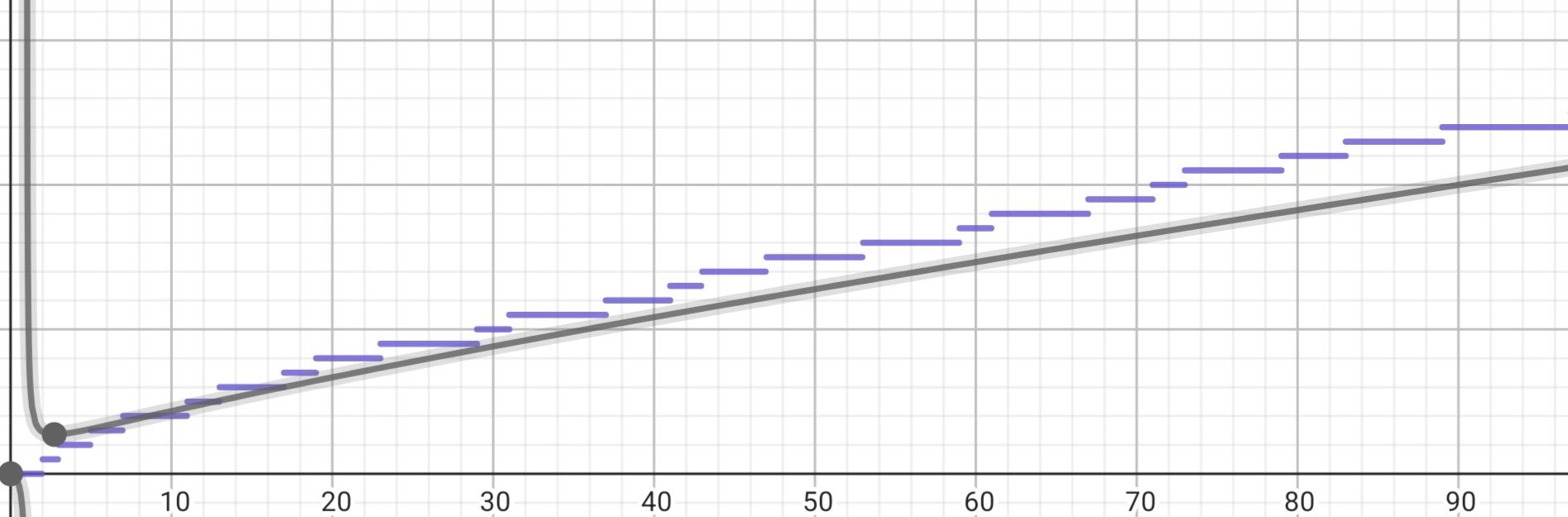

Basically, the prime counting function is a step function. It means that it’s not continuous. So, lets look at the graph of the prime counting function.

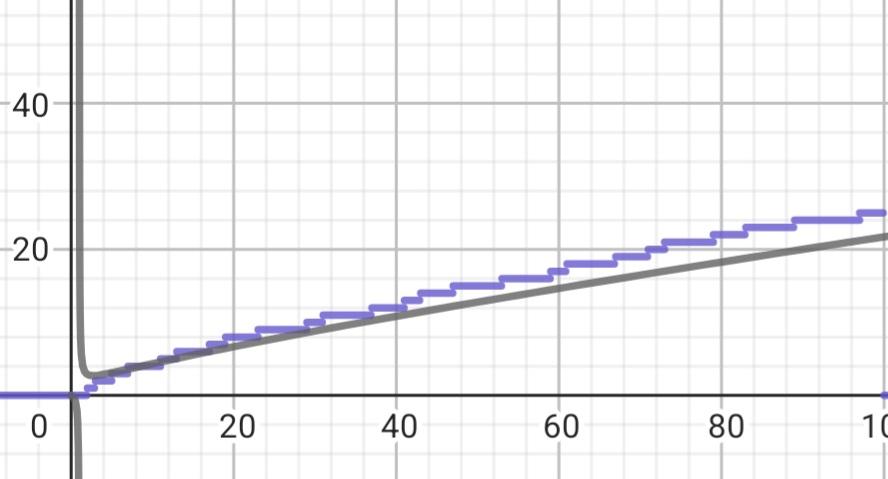

This function was introduced by Gauss in the 18th century and another thing Gauss showed was that you could approximate the value of the prime counting function with

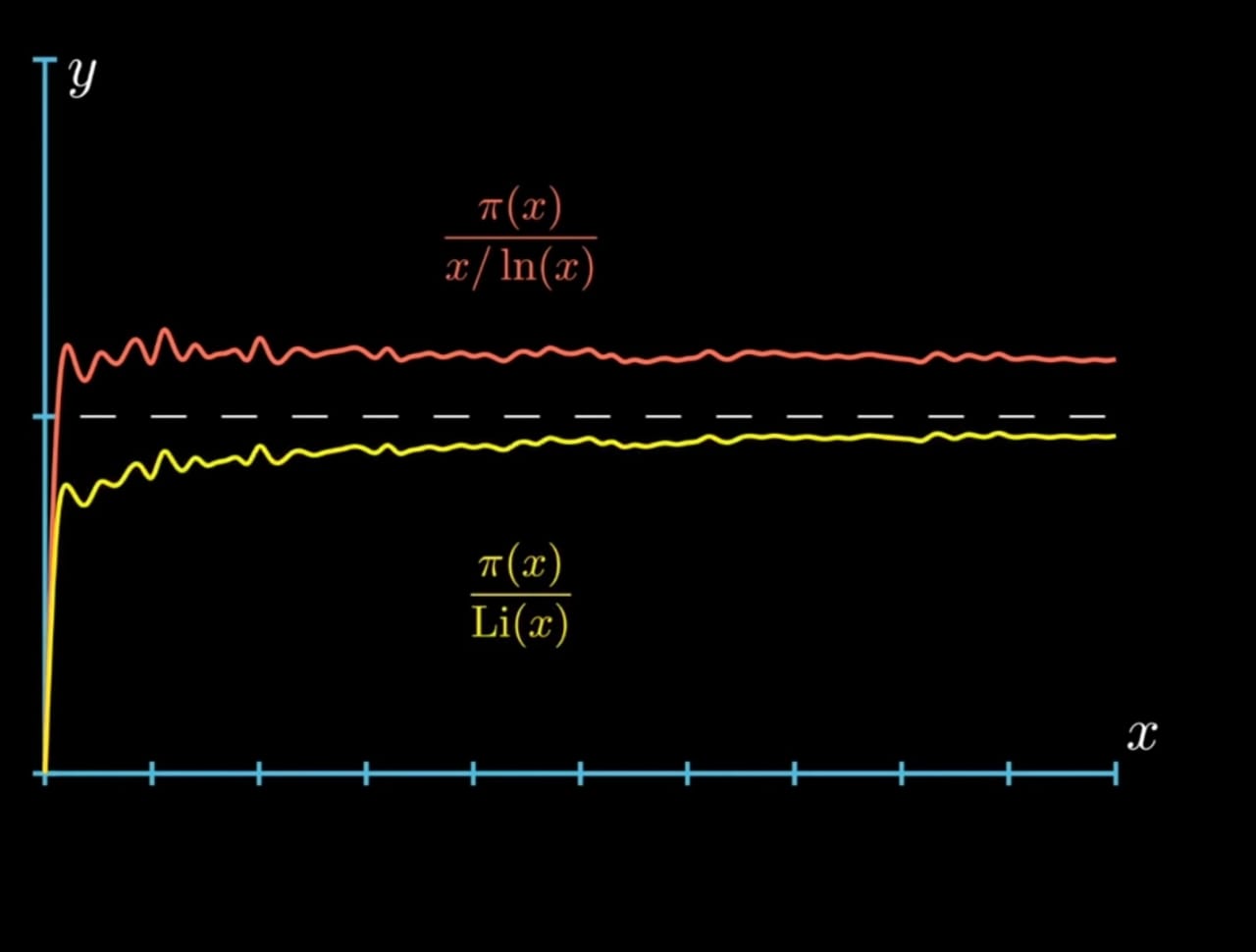

If you take a look at this graph, you can see how it closely approaches 1 as

Another result we can take from the prime number theorem i.e., the probability that a number chosen randomly from the set

Logarithmic Integral Function

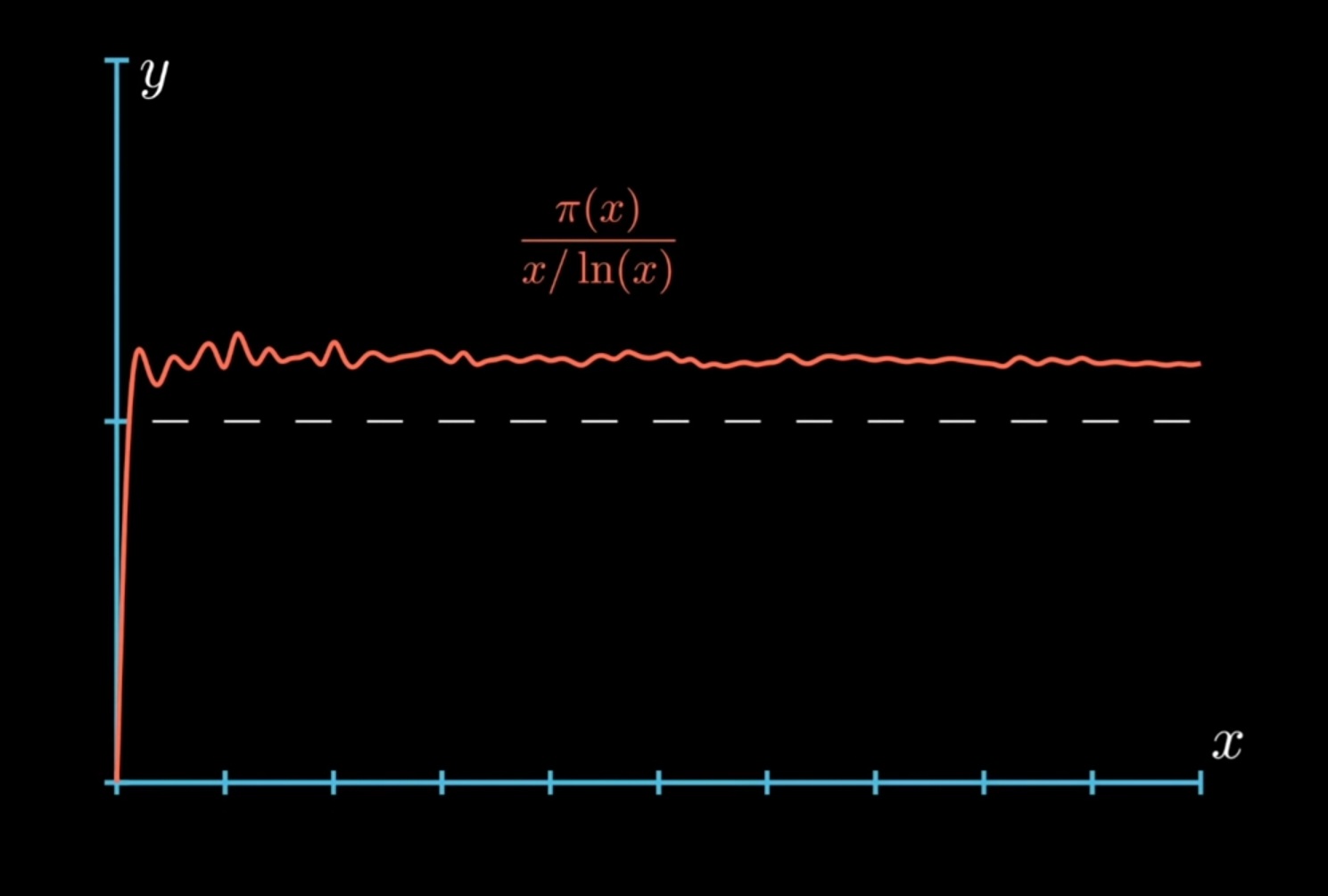

It actually turns out that

Since,

This way of approximating the prime counting function by the logarithmic integral function is was discovered by Dirichlet after Gauss mailed him prime number theorem.

Riemann Zeta Function

Bernhard Riemann was a German mathematician who studied fields like mathematical analysis, differential geometry, and number theory. He was one of the first who studied what happens when you extend the domain of zeta function from a real to a complex number.

Riemann zeta function is essentially the zeta function that we have discussed earlier except we extend the domain to the whole complex plane and it converges for real component which is greater than 1.

Why This is True

Let’s look at some input,

What this means for us is that the magnitude of each term in the Riemann zeta function only depends on real component and so the Riemann zeta function converges for

The term

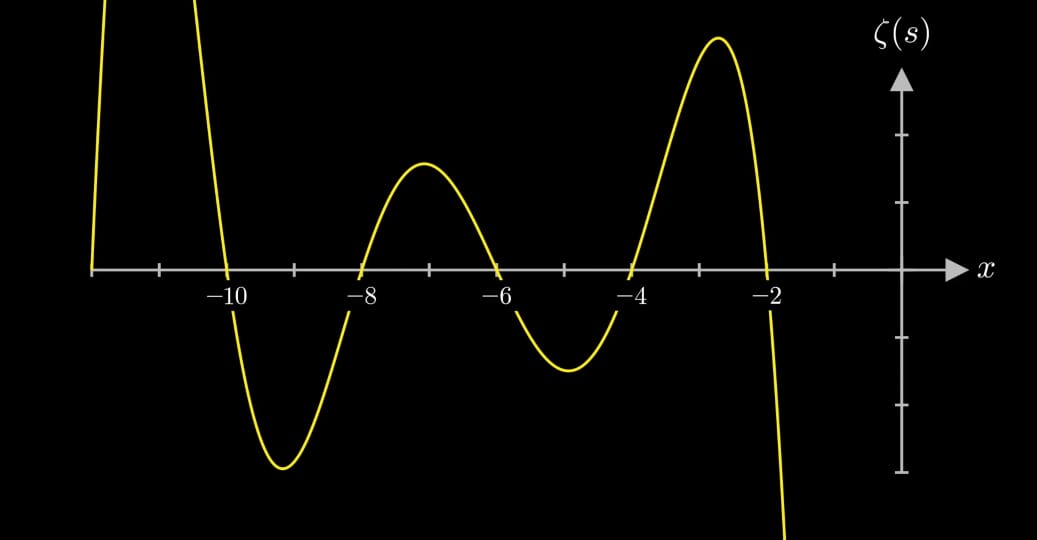

So, going back to the Euler product formula if the real component of the function is greater than 1 one of the products have to be equal zero for zeta to be equal to zero and this is impossible because of Euclid’s theorem which states that there are an infinite number of primes so the right component can not be equal to zero. That means the non-trivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function have have to have real component between 0 and 1. Let’s try to visualize them. The problem being that complex functions are like pretty hard to visualize. But this is our best we have showcase below.

We have fixed real component of input we’ve x-axis be the imaginary component. We have the graphs value of zeta vs imaginary part of zeta with real part 0.5. Notice that

Riemann and Primes

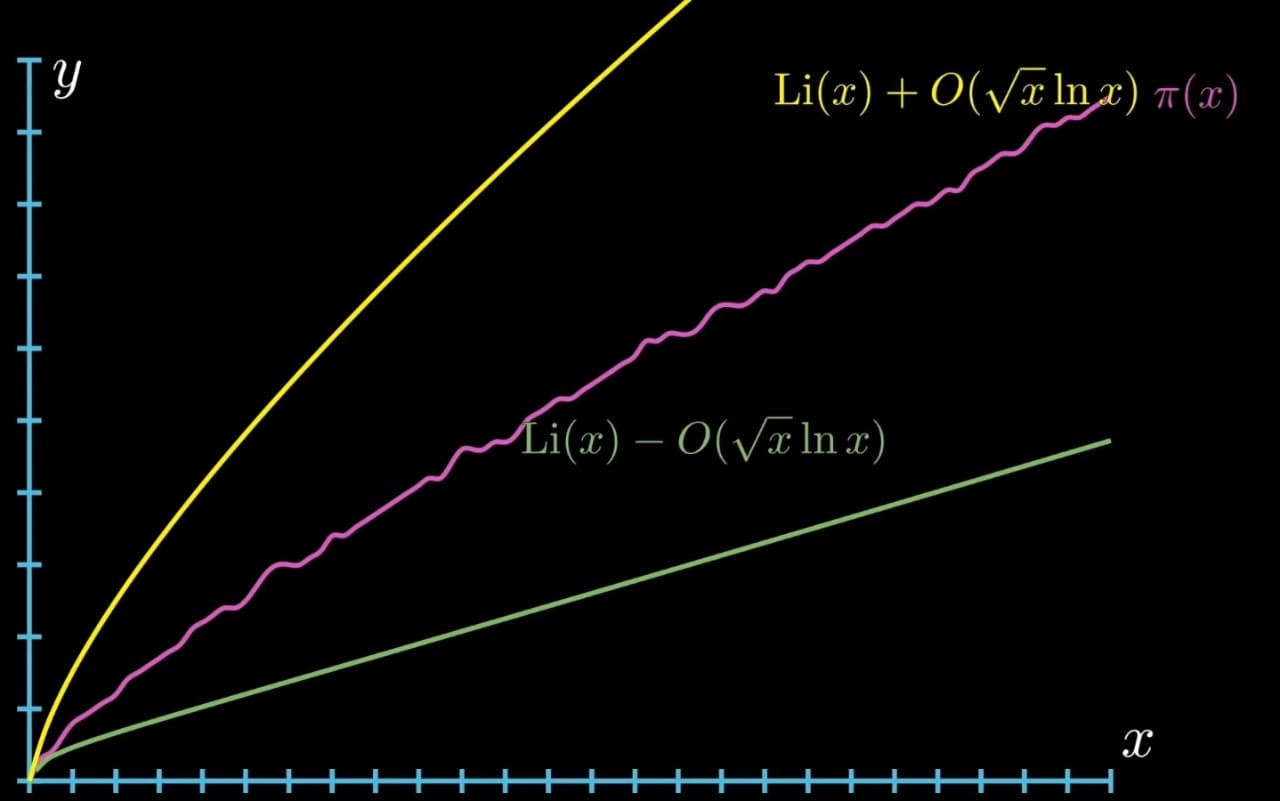

You’re wondering how all of this has any connection to the prime numbers. So, for this topic if we go back to the prime numbers theorem and recall how we could approximate the value of the prime counting function

A more direct question is how is the Riemann hypothesis and primes related?

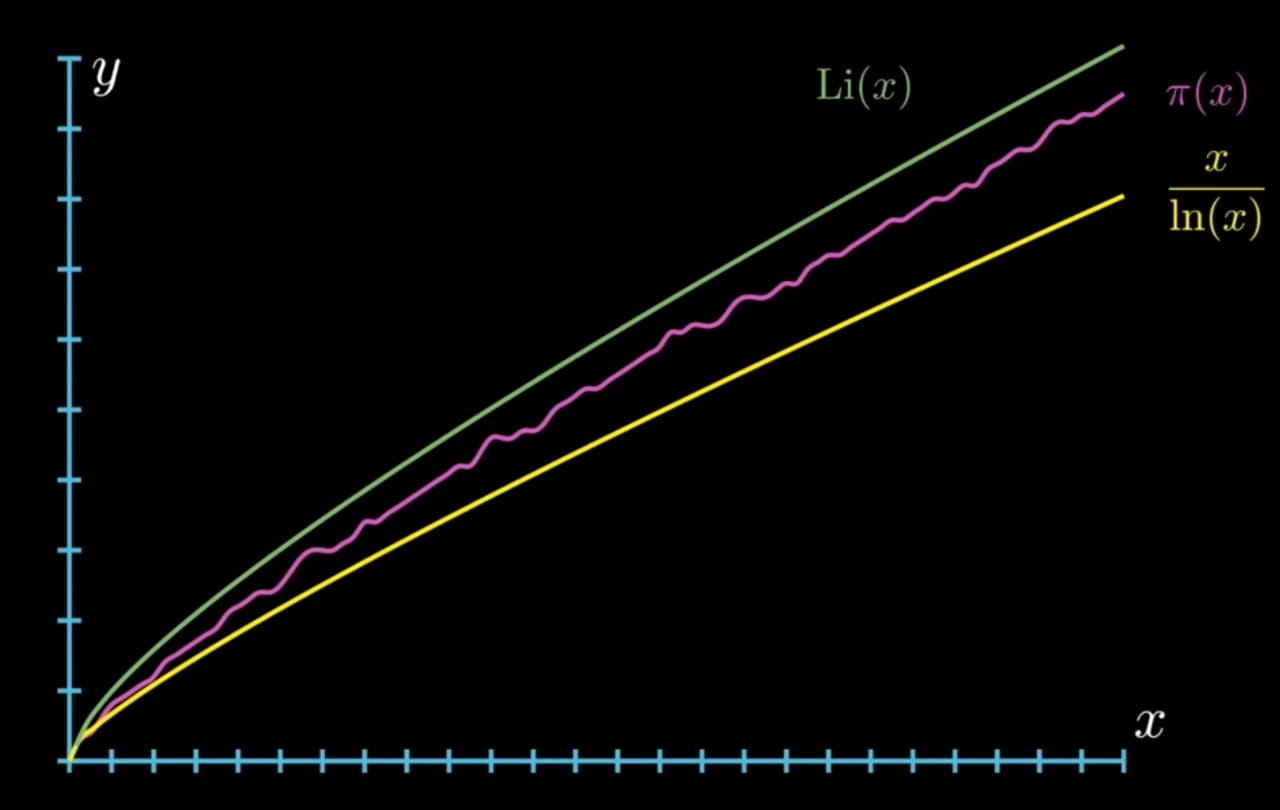

So, this would be where we discuss about Riemann explicit formula. Riemann explicit formula gives us a direct formula for the prime counting function and the second term over here i.e.,

Here the graph is about Riemann’s explicit formula using the first 200 non-trivial zeros of the zeta function. And you can see how the graph becomes better and better approximation. Using non trivial zeros of the Riemann-zeta function you can approximate prime counting function to have a pretty high accuracy.

Conclusion

The Riemann hypothesis remains an unsolved problem in the field of number theory each year attempts are made and hopefully, we can see a concrete solution to this problem in the future.

References

Conrey, “The Riemann Hypothesis,” Notices of AMS, March, 2003, 341-353.

M. Agrawal, N. Kayal and N. Saxena, “Primes is in P” Annals of Math., 160,(2004), 781-793.

Visualizing the Riemann zeta function and analytic continuation.