Sometimes you will never know the true value of moment until it becomes memory. So, let’s explore the idea of the moment in terms of mathematics and relate this to reality.

People, who belong to mathematics, statistics, and physics background, are familiar with the term moments but do you ever realize what is moment?

I was doubtful about my thoughts when I just completed my higher secondary studies and was admitted to the Statistics (Hons.) program as an undergraduate student. Professors often talked about the term moment. I was confused about what the term reveal actually. Is there any relation with the term moment which is discussed in Physics?

In this article, I’m going to express my concept and idea about moments using statistical sense as well as the concept of physics. And the end of this article I will try to relate that idea to the moment.

Statistical Notations:

Defining Expectation

Many frequently used random variables can be both characterized and dealt with effectively for the practical purpose by consideration of quantities called their expectation. For example, a gambler might be interested in his average winnings at a game, a businessman in his average profit on a product, a physicist in the average charge of a particle, and so on.

The ‘average’ value of a random phenomenon is termed its mathematical expectation or expected value. There are several senses in which the word “average” is used, but by far the most commonly used is the mean of an r.v., also known as its expected value. In addition, much of statistics is about understanding variability in the world, so it is often important to know how “spread out” the distribution is.

Mathematical Notation:

Given a list of numbers

More generally, we can define a weighted mean of

where the weights

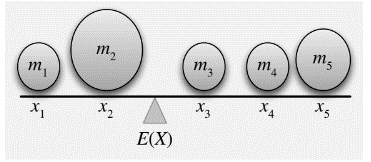

The definition of a discrete Random Variable is inspired by the weighted mean of a list of numbers, with weights given by probabilities.

Expectation of a discrete R.V. — The expected value (also called the expectation or mean) of a discrete random variable

If the support is finite, then this is replaced by a finite sum. We can also write,

where the sum is over the support of

In words, the expected value of

Let

which makes sense intuitively since it is between the two possible values of

This follows directly from the definition but is worth recording since it is fundamental.

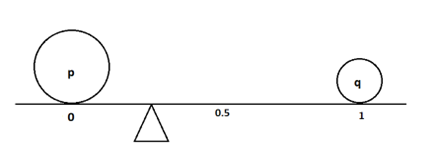

Center of mass of two pebbles, depicting that

Moments:

The moments of a r.v. shed light on its distribution. Everyone is quite familiar that the first two moments are useful since they provide the mean

Moments in statistics are popularly used to describe the characteristic of a distribution. It measures;

The

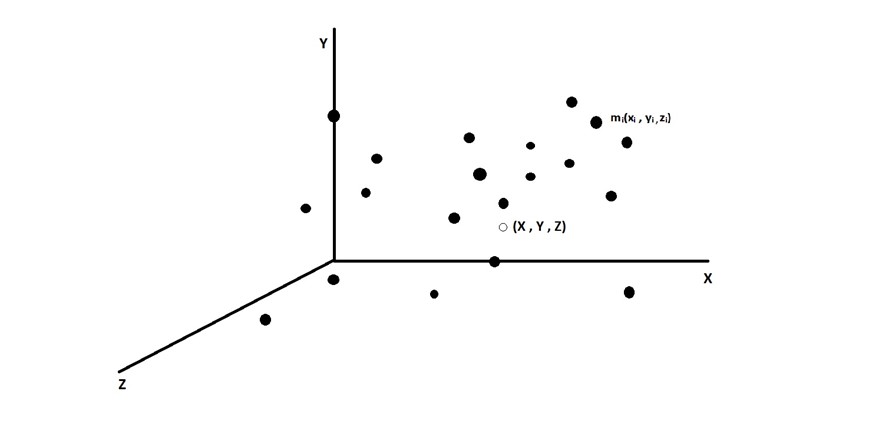

Usual Notation of Center of Mass

Let us consider a collection of

where

Now, locate the point with coordinates

Taking

Let

So, let us consider

Physics interpretation of moments i.e., the mean (first moment) of an R.V. corresponds to the center of mass of a collection of pebbles, and the variance (second central moment) corresponds to the moment of inertia about the center of mass.

This mathematical formula holds for continuous cases also. Because if summation notation defines discrete case then there might be the continuous case which is true.

Center of Mass for Continuous Bodies

If we consider the body to have a continuous distribution of matter, the summation in the formula of the center of mass should be replaced by integration. So, we don’t talk of the

The integration is to be performed under the proper limits so that as the integration variable goes through the limits, the elements cover the entire body.

This is the absolute beauty of moments. Mathematics has a beginning but there is no end. It is just like an expanding universe because both have no boundaries and don’t allow perfection. It is the only place where truth and beauty bring revolution.

References

Introduction to Probability by Jessica Hwang and Joseph K. Blitzstein.

Fundamentals of Mathematical Statistics by S. C. Gupta and V. K. Kapoor.

Concepts of Physics by H. C. Verma.