Thoughts without content are empty, intuitions without concepts are blind.

Introduction

One of the most remarkable aspects of the human brain is its ability to recognise patterns and describe them. Among the hardest patterns we’ve tried to understand is the concept of turbulent flow in fluid dyanamics. The German physicist Werner Heisenberg said,

“When I meet god, I’m going to ask him two questions: why relativity and why turbulence? I really believe he will have an answer for the first.”

As difficult as turbulence is to understand mathematically, we can use art to depict the way it looks. In June 1889, Vincent van Gogh painted the view just before sunrise from the window of his room at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in some Saint-Remy-de-Provence, where he’d admitted himself after mutilating his ear in a psychotic episode.

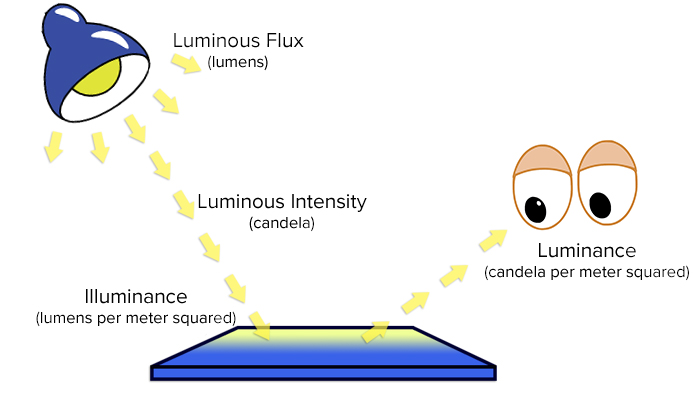

Luminance

In “The Starry Night”, his circular Brushstrokes create a night sky filled with swirling clouds and eddies of stars. Van Gogh and other impressionists represented light in a different way than their predecessors, seeming to capture its motion, for instance, across sun-dappled waters, or here in starlight that twinkles and melts through milky waves of the blue night sky. The effect is caused by luminance, the intensity of the light in the colors on the canvas. The more primitive part of our visual cortex, which sees light contrast and motion, but not color, will blend two differently colored areas together if they have the same luminance. But our brains’ primate subdivision will see the contrasting colors without blending. With these two interpretations happening at once, the light in many impressionist works seems to pulse, flicker, and radiate oddly. That’s how this and other impressionist works use quickly executed prominent brushstrokes to capture something strikingly real about how light moves.

Definition

Luminance is a photometric measure of the luminous intensity per unit area of light traveling in a given direction. It describes the amount of light that passes through, is emitted from, or is reflected from a particular area, and falls within a given solid angle. The candela per square meter is the unit of luminance in the International System of Units (

The luminanceLuminance of the sun.

A filament of a clear incandescent lamp.

Fluorescent lamp.

Road surface under artificial lighting

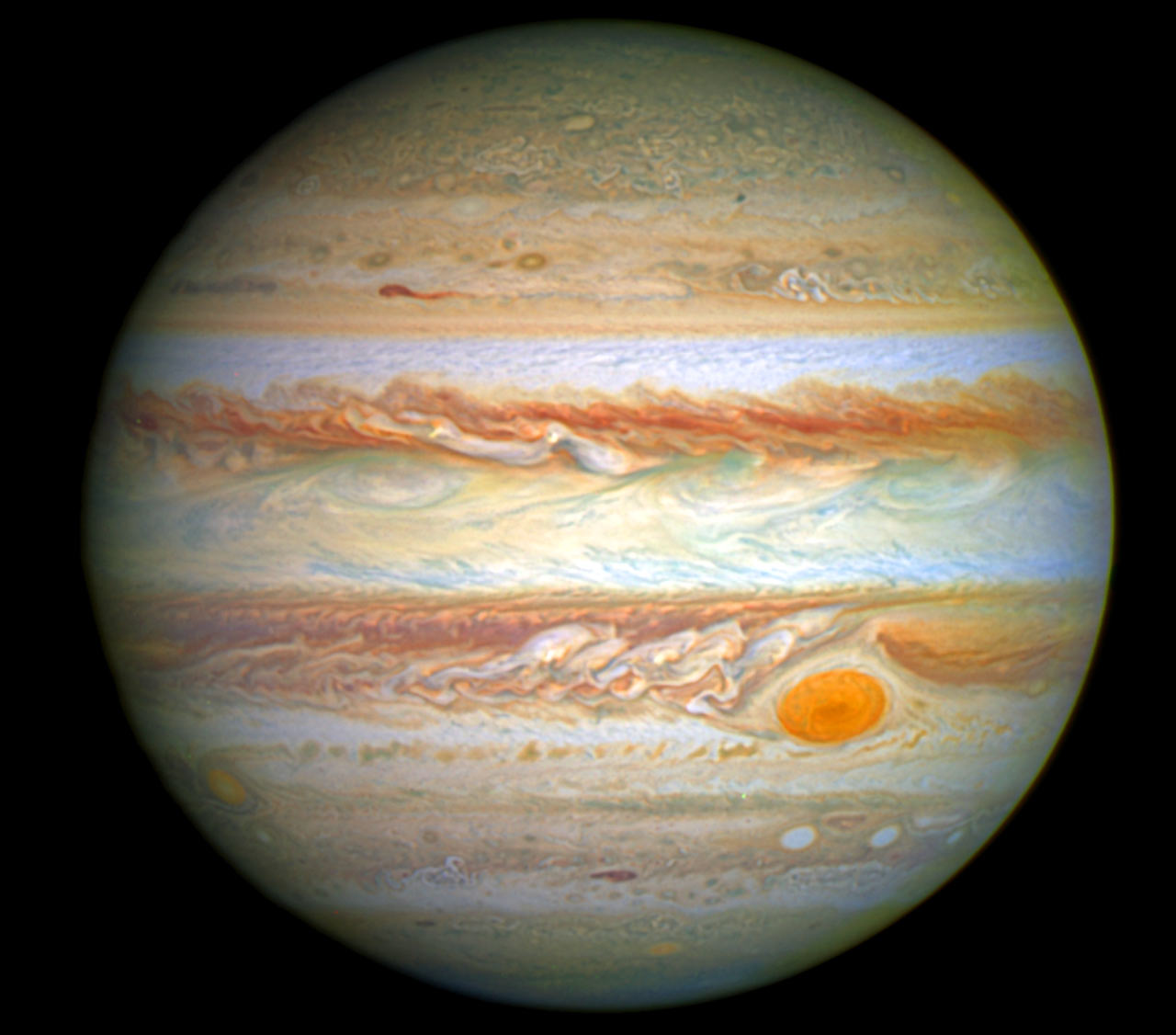

Turbulence

60 years later, Russian mathematician Andrey Kolmogorov furthered our mathematical understanding of turbulence when he proposed that energy in a turbulent fluid at length R varies in proportion to

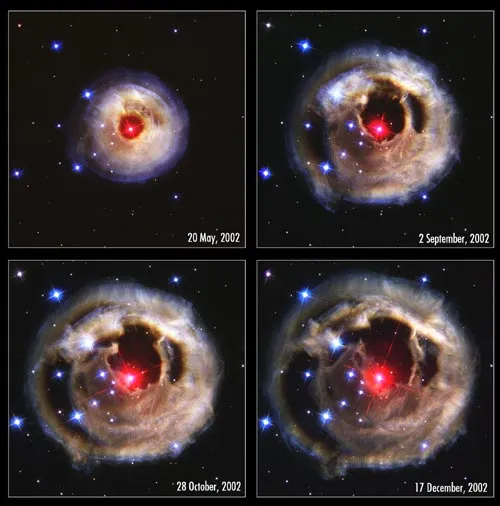

In 2004, using the Hubble Space Telescope, scientists saw the eddies of the distant cloud of dust and gas around a star, and it reminded them of Van Gogh’s “Starry Night”.

Van Goghs Luminance

This motivated scientists from Mexico, Spain, and England to study the luminance in Van Gogh’s paintings in detail. They discovered that there is a distinct pattern of turbulent fluid structures close to Kolmogorov’s equation hidden in many of Van Gogh’s paintings. The researchers digitized the paintings and measured how the brightness varies between any two pixels. From the curves measured for pixel separations, they concluded that paintings from Van Gogh’s period of psychotic agitation behave remarkably similar to fluid turbulence. His self-portrait with a pipe, from a calmer period in Van Gogh’s life, showed no sign of this correspondence. And neither did other artists’ work that seemed equally turbulent at first glance, like Munch’s “The Scream.” While it’s too easy to say Van Gogh’s turbulent genius enabled him to depict turbulence, it’s also far too difficult to accurately express the rousing beauty of the fact that in a period of intense suffering, Van Gough was somehow able to perceive and represent one of the most supremely difficult concepts nature has ever brought before mankind, and to unite his unique mind’s eye with the deepest mysteries of movement, fluid, and light.

Reference

Davidson, P. A. (2004). Turbulence – An Introduction for Scientists and Engineers. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198529491.

Kolmogorov, Andrey Nikolaevich (1941). “The local structure of turbulence in incompressible viscous fluid for very large Reynolds numbers”. Proceedings of the USSR Academy of Sciences (in Russian). 30: 299–303.

The Interesting Math Behind The Famous Painting “The Starry Night”.